GREENWASHING FACT SHEET SERIES

What the aviation industry tells you and what they DON’T tell you

What we need to know about decarbonisation promises and false solutions

By taking a closer look at what the industry tells us and what they don’t tell us, in our new fact sheet series we debunk common misconceptions and look behind the green curtain of their promises

Read here an outlook and summary of the fact sheets:

Click below to download the fact sheets or read online summaries further below.

- Summary

- Efficiency

- Electric Flight

- Hydrogen

- Biofuels

- E-fuels

- Net Zero

- Carbon Offsets

- Negative Emissions Technologies

Summary: Aviation Greenwash vs. Reality

“Greenwashing” is misinformation intended to mislead others about the environmental impact of activities.

Globally, the aviation sector plans to triple in size by 2050 which would see aviation fuel consumption and therefore greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, double.

Governments, lobbied by the sector, use unrealistic and distracting promises of technological solutions and offsets to greenwash this growth. They also use economic growth and job arguments to justify subsidies and tax breaks for airports, airlines, manufacturers and fossil fuel companies.

In our series of Fact Sheets, we examine these claims and debunk common myths and misconceptions.

Efficiency Improvements

Aircraft efficiency refers to the amount of fuel burned (and emissions produced) by an aircraft in order to transport its payload (passengers or cargo) a given distance (e.g. one kilometer). Efficiency improvements (i.e. reductions in fuel burn) are achieved by optimising the design of the aircraft, the engines, the airline operations (e.g. the flightpath) and by increasing the amount of passengers/cargo carried onboard the aircraft.

CO2/passenger-km is proportional to efficiency (fuel/pass-enger-km).

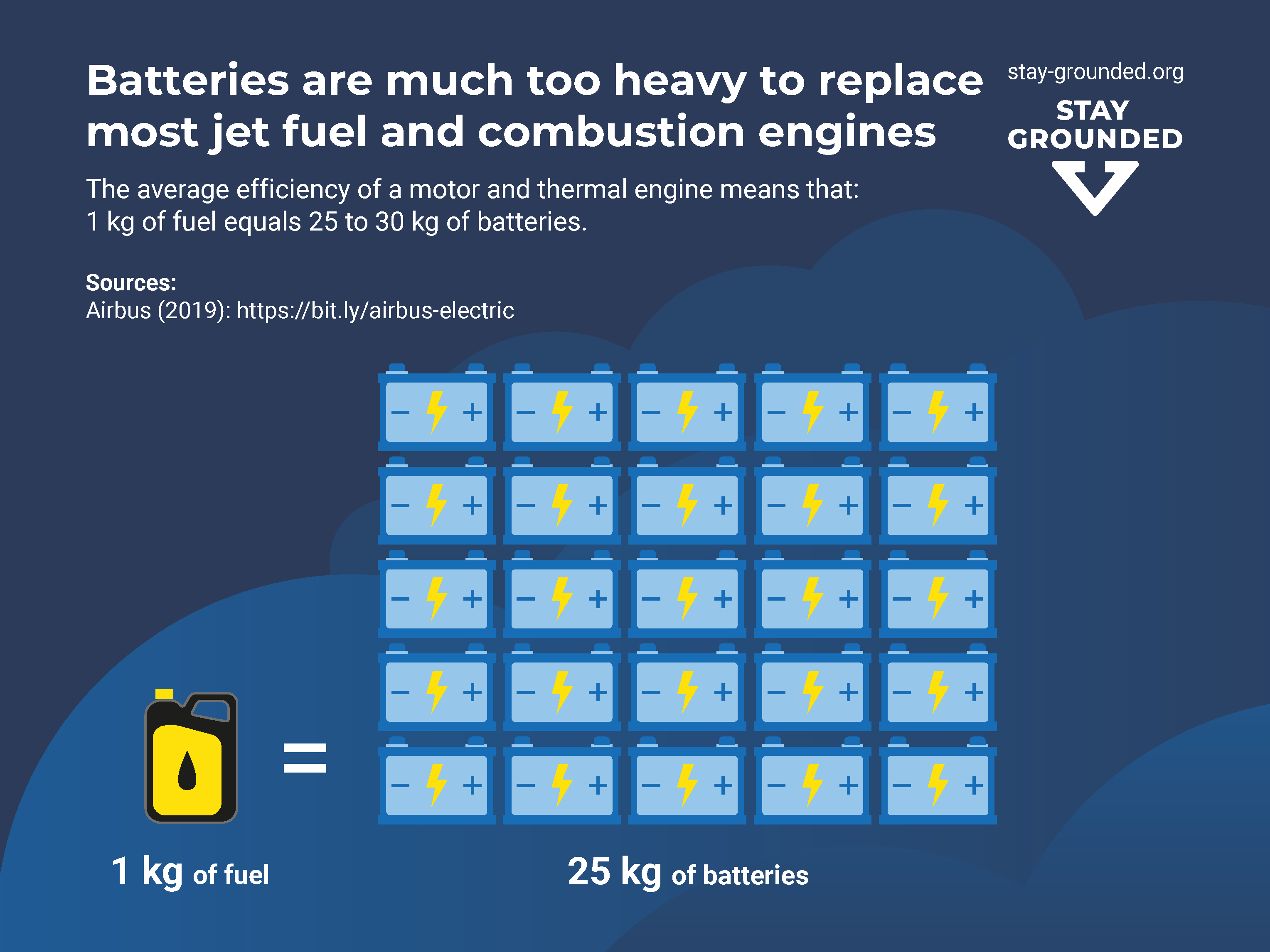

Electric Flight

Hydrogen Flight

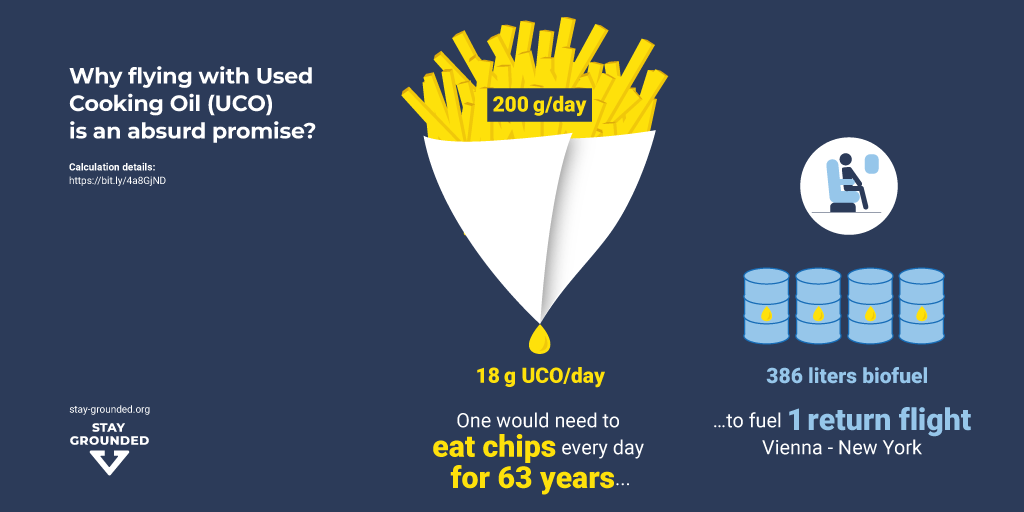

Biofuels

Aviation biofuel is a liquid hydrocarbon fuel that can be used with existing aircraft blended with fossil kerosene. Like e-fuel (see Fact Sheet #5 Synthetic e-fuels), the sector calls it a “Sustainable Aviation Fuel” (SAF), which it is not, as we demonstrate in this fact sheet.

Biofuels for aviation are produced from biomass sources and hydrogen. First generation biofuels use agricultural crops. Due to their drawbacks, the sector is mandated by European legislation to use so-called “waste and residues”, either industrial, food, farm and forestry.

At present, the only aviation biofuel of this kind proven at scale, HEFA (Hydrogenated Esters and Fatty Acids), are made from feedstocks labeled as “used cooking oils” or “animal fats” (from slaughterhouse operations).

However there is rampant mislabeling of these feedstocks, including, for example, virgin palm oil labeled as used cooking oil. So-called “advanced biofuels” from lignocellulosic biomass (wood, straw…) have never been and are unlikely to ever be technically proven at scale. Hydrogen, although rarely mentioned, is required in all certified aviation biofuel production processes, but is today mostly produced from fossil fuels (see Fact Sheet #3 Hydrogen flight).

Synthetic Electro-fuels

Alternative jet fuels or so-called “Sustainable Aviation Fuels” (SAF) are liquid hydrocarbon fuels that can be used with existing aircraft in place of kerosene produced from fossil fuels. The industry’s premise of the sustainability of these fuels is to create the fuel using CO2 taken from the atmosphere, rather than using fossil fuels extracted from deep underground that will then emit additional CO2 to the atmosphere when burned. The argument is that blending these fuels with fossil fuels would thereby reduce emissions.

Alternative jet fuel can be broadly categorised into two varieties:

- Biofuels produced from biomass sources (see Fact Sheet 4)

- Synthetic electro-fuels (e-fuels) produced using electricity (explained below)

Synthetic electro-fuels or “e-fuels” can be produced by combining hydrogen with carbon to create a liquid hydrocarbon. In order to minimise emissions, hydrogen must be extracted from water by electrolysis using renewable energy; and carbon must be extracted from the air using a process called ‘Direct Air Capture’ (DAC). These can then be combined, to form a hydrocarbon fuel using Fischer-Tropsch (FT) synthesis1. The latter processes must also be powered with renewable energy.

E-fuels are also known as “Synfuels” or Power-to-Liquid (PtL) fuels. E-fuels, as well as biofuels, are drop-in fuels that could be blended with conventional fossil jet fuel (kerosene) and used by the existing fleet.

At first sight, e-fuels seem to be the ultimate weapon for decarbonising aviation: they should be able to be used directly in all types of current aircraft, whatever their range; they do not suffer from raw material limitations because they are made from water and air, which are very abundant resources; and the electricity required could itself be generated from the sun and wind, which are very abundant energies. So why are there no aircraft powered by these fuels yet and very few for another ten years or so? Mainly because the production of e-fuels is extremely wasteful of energy. It would deprive other sectors needing to decarbonise as there will not be enough renewable energy available to satisfy all the requirements in the next decades. Also because this is a new industry starting almost from scratch, that still needs to complete process development and set up a whole new sector.

Net Zero & Carbon Neutrality

Reaching “net zero” targets is currently the central goal set in nearly every climate strategy – be it industry or government. For its part, the aviation sector has committed to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

According to the IPCC1, net zero CO2 emissions are achieved when any remaining anthropogenic CO2 emissions are balanced globally by anthropogenic CO2 removals. This means with the net zero concept, some “hard-to-abate” emissions are still allowed, provided that equivalent quantities of CO2 are removed from the atmosphere. Net zero CO2 emissions are also referred to as carbon neutrality. When all greenhouse gases are taken into account, this is referred to as net zero emissions.

Balancing residual emissions is promised via Carbon Dioxide Removal; this is a range of processes that remove CO2 from the atmosphere in addition to the removal via natural carbon cycle processes. It can be achieved either by increasing biological or geochemical sinks of CO2 or by using industrial processes to capture CO2. Carbon Dioxide Removal is one of two types of carbon offsets2 besides credits for ‘avoided’ emissions.

Carbon Offsets

A carbon offset is a ‘unit’ of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that is (allegedly) reduced, avoided, or removed from the atmosphere by one entity and purchased by another entity to try and compensate for its own emissions.

Carbon offsets play an important role in many current emission reduction plans and can be part of cap and trade schemes like in California. Based on projects that are mostly located in the Global South, offsets are being used by states and companies (mainly in the Global North) to achieve compliance. Most trades take place on dedicated carbon markets.

The aviation sector makes extensive use of carbon offsetting. The responsible UN body, the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organisation), has agreed upon a common scheme for international flights called CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation).

Some countries or regions have specific offset schemes

for flights within their boundaries. Air travellers may also be offered to purchase offsets when they buy tickets from airlines or travel agencies, or they might even come included in their package. Airports are also directly utilising offsets to cover ground emissions and using that as an incentive for people to use their ‘Green Airport’, irrespective of aircraft emissions.

Negative Emissions Technologies

Like most governments and many sectors, the aviation sector has an objective of “Net-zero” emissions by 2050. This will not meet Paris Agreement goals without ambitious near-term reductions of emissions they appear unable or unwilling to deliver (See Fact sheet #6: Net Zero & Carbon Neutrality). They justify continuation of high emission levels or even growing emissions by planning for the use of negative emissions [also referred to as ‘Carbon Dioxide Removal’ (CDR) or ‘Greenhouse Gas Removal’ (GGR)] in the fairly distant future. However, as this fact sheet explains: this is a dangerous and reckless strategy.

“Negative Emissions Technologies” (NETs) refers to industrial processes (rather than natural processes such as tree growth) which actively remove carbon dioxide (CO2) by capturing it from the atmosphere and storing it, supposedly permanently. The technologies usually proposed are: (1)

- Direct Air Carbon Capture & Storage (DACCS) – capturing CO2 directly from the atmosphere via industrial processes and storing it underground.

- Bioenergy with Carbon Capture & Storage (BECCS) – producing energy from biomass, then storing part of the resulting carbon underground or in the soil.